10. The rapid evolution of cowpea weevils’ willies

The Callosobruchus maculatus, or cowpea weevil, has a penis (shown above) with spines that stick out in all directions. It’s not much fun for the female, so to limit the damage, the female’s vaginal wall is reinforced and during sex, she attempts to kick the male away. Literal battles of the sexes occur frequently in nature: spines, injury, rape and attempts to seal up the vagina after mating are common. A number of possible explanations have been suggested: males with large spines stay stuck to the females for longer, perhaps allowing them more time to fertilize the ova, or perhaps to help scrape out the sperm of a previous partner. Or perhaps, if a female’s genital area is severely damaged, she can’t mate with other males – another advantage for the male.

Australian biologists once conducted an elegant experiment with a species of beetle that normally has a polygamous lifestyle. The researchers put two virgin beetles together and kept them away from others, forcing them to be monogamous. They did that with an entire beetle population, and repeated it with offspring produced, with the generation after that, etc. After about eighteen generations (approximately a year for this species), the males in the monogamous population had smaller family jewels, which had shorter spines. As soon as males did not have to compete with other males, the situation changed to the advantage of males with smaller, less destructive genitals.

9. The mystery of the human genitals

As we mentioned above: spines on penises are quite common in the animal kingdom, and not just among insects. Cats make such a lot of noise at night because toms have barbed penises. Chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest relatives in evolutionary terms, have tiny horns on the top part of their penises. Why do humans rarely have these kinds of spines?

“We know which pieces of DNA are responsible for penile spines and at what point they changed in evolutionary history. But we don’t know why they changed, and why specifically in humans. The genitalia of ovulating female chimpanzees swell to increase the depth of the vagina and probably help the females to decide – consciously or subconsciously – which male may impregnate them. But why is it like that for them and not for us?” Schilthuizen remarks.

Despite the interest many people have in sexual intercourse, very little is known about the how and why of our genitals. “There have been a few experiments with radiosondes and MRI scans, but they are certainly not carried out in every laboratory in the world due to cultural barriers”, the biologist explains.

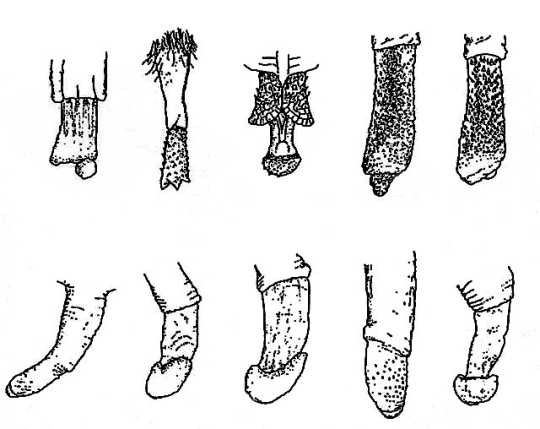

8. The diversity of galago genitals

Galagos are African prosimians; at first sight, there seem to be only a few species, though closer inspection reveals that there are many more if they are classified according to their wedding tackle. Botanists and insectologists had been distinguishing species by examining genital differences for years but mammalogists had some catching up to do in that respect. Accordingly, a large number of new species have been discovered in recent years. And the fact that the stuffed specimens in museums usually have dried, wrinkled equipment does make it any easier to examine them.

The nagapies family– as they are called in Afrikaans – have an extensive collection of pizzles between them, with spines or without spines, bumps in different places or wedge-shaped glans. Just as music lovers love variations on a theme, taxonomists derive pleasure from revealing the diversity of these various animals, even if the differences are only between the creatures’ hind legs.

7. Hermaphrodite snails and their love darts

“If you have two genders in one animal, sex is twice as interesting”, says Schilthuizen, quoting a colleague in his book. Cowpea weevils may fight the battle of the sexes between individual animals, in snails, the battle occurs in a single animal, and as a consequence, the evolution of the genitals has had complete differently results. The Chromodoris reticulata nudibranch has a detachable penis which it leaves behind after mating and the slug Limax has a penis which measures six times the length of its body and can absorb and exude sperm.

“The most exciting thing is the love dart”, says Schilthuizen. “If you know what to look for, you can find white calcareous darts in your garden at this time of year: they are a few millimetres in length and produced by ordinary snails.” The darts send hormone-like substances to the mate’s body so the protagonist can make sure that the organ that digests sperm in its mate cannot function properly, leaving more of its own sperm to fertilize its mate’s eggs. “Next time you have escargots and you feel something crunchy between your teeth, you’ll know what it is.”

6. Rove beetle penises are thwarted by mazes

An unusual result of the battle of the sexes is the maze-like vagina which allows females retain control of fertilization. To illustrate, female ducks have all sorts of internal false leads and sharp turns to send the penises of raping drakes off course. A more extreme example is the rove beetle Aleochara tristis, of which the males have thin whip-like penises that are almost three times as long as their bodies. When not in use, the penis is rolled up but during copulation it is required to proceed along a complex route in the female’s body. When the male withdraws, it has to be very careful not to get its penis in a twist.

5. The walrus has a weapon

“The collection at Naturalis includes a number of walrus bacula that were used by the Inuit as weapons”, continues Schilthuizen. One species of walrus, now extinct, had bacula measuring almost one and a half metres, but even at sixty centimetres, modern-day walrus ossa penis are impressive.

A penis bone is in fact very common: dogs have them; each species of squirrels has its own version – sometimes full of spines that support the fleshy part of the penis; monkeys have them – some species can create an erection by simply adjusting the bone to the right spot. Male chimpanzees and gorillas have a bone between their legs, so why don’t humans? Schilthuizen replies: “There are so many things to discover about the species we think we know best.”

4. Porking with corkscrews

“Asymmetric penises are quite common: pigs have them, but so do other domestic animals such as sheep and camels, but nobody knows why. Maybe it allows the females to decide which male may get her pregnant, just like rove beetles and ducks. Presumably, sexual selection according to unusual tactile signals has something to do with it. In the same way that peahens want the peacock with the finest tail feathers, perhaps sows want a male partner with a pizzle that feels the most unusual. But there could be something even more interesting going on”, says the professor, shrugging his shoulders. “I have not heard of any systematic studies that have examined whether sows are asymmetrical. It’s possible that the penises try to get round the females’ control mechanisms and that why they take that shape. It’s strange that no one has systematically researched these animals that are so close to us.”

3. The female of the Brazilian bark louse has a penis

Neotrogla males wrap their seed up in a very nutritious package and the female has to enter the male’s body with a “gynosome”, a female organ that looks very much more like a penis than many other real penises in the animal kingdom. Females with pseudo-penises are not unique in nature – the female spotted hyena has a larger penis than you, for instance – but Neotrogla is one of the few species that actually penetrate the male.

2. Squids ejaculate torpedoes

Neotrogla is not the only creature to add a little something to its sperm: the males of all sorts of animals don’t ejaculate fluid but “spermatophores”, which literally means “sperm carriers”. They can be quite complex; many species of squid produce a kind of torpedoes that can swim independently and penetrate the females. They do not need to enter via the vagina, as squids don’t have them. Any hit is fine for a squid (or, in unfortunate cases, humans who eat them), and once inside, the ejaculated matter ejaculates again, releasing the real sperm cells. It is likely that this independent seed is a solution for the problems of mating in turbulent water.

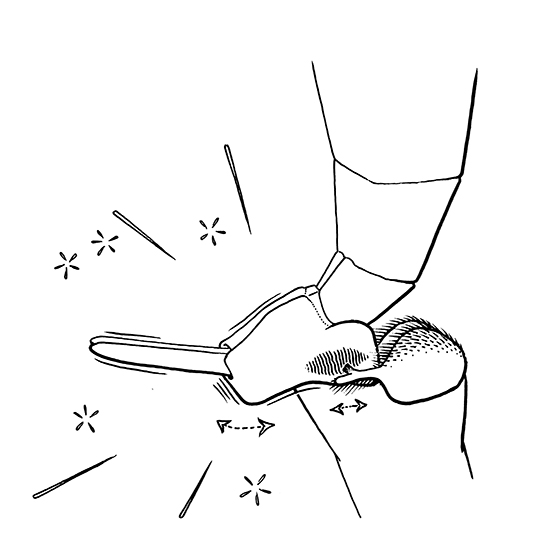

1. The Bellardina crane fly uses musical vibrator

The arms race between the sexes has a simple reason: one gender must invest far more in offspring than the other. A male human produces some billion sperm cells per month while a female can only produce one fertile ovum. If that is fertilized, she cannot become pregnant again for another year so she has every reason to be particular. The same fastidiousness can be found throughout the animal kingdom: male frogs croak, peacocks wave their tails and giraffes beat each other with their necks – all to impress the ladies.

The very weirdest stimulating willy belongs to the Bellardina sp., a crane fly from Central America. The penis is wrapped in a set of plates and tubes into which the female bulges are to fit. The end has a sort of washboard with two claw-like bulges that abrade the washboard, producing an audible tone – a vibration the female must feel through its genitals as it mates. “It’s a tangible mating call rather than audible one, as it were” declares Schilthuizen.

Menno Schilthuizen

Viking Books, 256 pages, €25.99